TK Maxx in Karl-Marx-Stadt

This piece was written in October 2011 after the church authorities decided to close St Paul’s cathedral and start legal proceedings against Occupy London protestors camped outside. That summer, I’d spent a few days in Leipzig, where the church had played a leading part in protests against the DDR government which eventually led to the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the contrast seemed… stark.

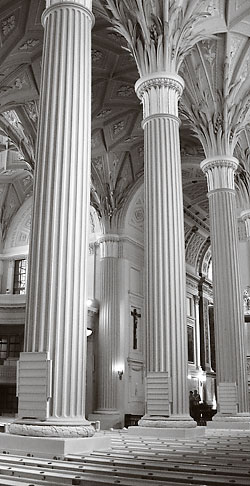

Pinched between narrow streets whose medieval awkwardness makes it difficult to stand back and frame a photo, the Nikolaikirche, Leipzig’s oldest church, is outwardly pleasing but plain. So to step through the small west door from Nikolaistrasse’s crowded pavement is to suffer a sudden dislocation of the senses, for instead of being filled with gothic gloom and a mood of sombre sanctity, the church reverberates with light: all around, surfaces glow cream and gold, apple green and rose pink, and elegant white-painted pews line a classical avenue of fluted columns whose tops dissolve into fronds of palm that sprawl across an intricately coffered ceiling. It’s the result of a late eighteenth-century refurbishment, and is extraordinary.

Also extraordinary is the black and white photograph I now have in front of me: in it, the same pale pews are clearly visible, but here they’re filled, end-to-end, with people. Others, unable to find a seat, lean back against the bench ends, or squat or sprawl in the aisle. Young and old sit side-by-side and gaze, warily defiant, at the camera. The date on the photo is Monday, 30th October, 1989, the first day of the last week before the Wall fell.

Mondays were important in Leipzig, and particularly in the Nikolaikirche. Since 1982, Monday had been the day for the church’s weekly Friedensgebete, “peace prayers”; people would come to the church not just to pray, but to campaign for demilitarisation and an end to the Cold War arms race. Later, they would talk too of environmentalism, human rights and democracy. Protestors risked the wrath of the Stasi, but the church was the one institution in the DDR that seemed to offer protection. Early in 1988, Pastor Christian Führer held a meeting at the Nikolaikirche supporting those who wished to leave for the West. By late summer, others at the Monday gatherings were espousing a more radical idea: they wanted to stay, not get out, but in a free and democratic Germany.

In January 1989, Pastor Führer pinned a text to the church’s information board demanding justice in the DDR – it was, he wrote, “our challenge, our expectation”. The following month, a 500-strong rally calling for democracy and freedom was broken up by police, and pressure increased on the Nikolaikirche to discipline those it sheltered. But the Friedensgebete continued. On 25th September, after the previous Monday’s meeting had ended with police forming a ring around the overflowing church and making many brutal arrests, Pastor Christoph Wonneberger preached a sermon criticising state violence and demanding democratic change through peaceful means; at the end of the service, with police lines blocking the way to the city’s traditional rallying point of Marktplatz, crowds headed hand-in-hand to nearby Karl-Marx-Platz, and from there walked around the city’s ring road to the Reformkirche and back, gathering support until they were 8,000 strong. The following Monday, 2nd October, 20,000 marched, this time continuing to the Thomaskirche on the far side of the city, where they were met by riot shields, helmets and truncheons.

On Monday, 9th October, 700 government agents were sent to the Nikolaikirche to “prevent provocations”; for most, it would be the first time they’d experienced the prayer meetings first-hand, and many would find themselves won over by what they heard. By mid-afternoon, the church was full, and later arrivals were left to gather outside, or to walk to the city’s other churches, seven of which were now holding their own peace prayers. By 5pm all the churches were full, and crowds clustered outside. In neighbouring streets were police with dogs, and rumours circulated of troops massing in the suburbs. And yet, once the prayers were over, 70,000 marched around the ring road from Karl-Marx-Platz carrying placards and candles. As Erich Mielke, head of the Stasi, later said: “We were prepared for everything, but not for prayers and candles.”

On Monday, 16th October, 150,000 walked through the city. On the 23rd, there were 300,000. A week later, the photo I’m now looking at was taken.

The Berlin Wall came down on 9th November. I have a piece on the windowsill here, a jagged grey chunk, smooth on one side, crystalline on the other, hacked off by a friend who was on the Wall that night and posted it to me in a jiffy bag. You can buy lumps of “Mauer” all over Berlin these days, but I know this piece is real, because my friend was there, with his hammer: you can even see the orange and pink fizz of graffiti on it.

Obviously Leipzig wasn’t alone – half a million people demonstrated in Berlin five days before the Wall fell. But Leipzig was the first, and inspired what came after, and the Nikolaikirche is where Leipzig’s rebellion began. And it wouldn’t have happened without some very brave people, and some very brave churchmen standing up for what they thought was right.

Travelling through Saxony this summer, we found Leipzig a delightful surprise. The old trams still rattle round the ring road and the suburbs can be forbidding and grim, but the city centre bustles and gleams, and our hotel, almost opposite the Nikolaikirche, had tables out on the pavement for breakfast. The dusty gaps between the shops are being filled and there’s a new railway under Marktplatz. The city, it seems, wants to move on. The DDR Museum is empty, and Karl Marx has been disowned: his Platz in Leipzig has been handed back to Augustus and at Chemnitz, the former Karl-Marx-Stadt a few stops down the line, the first thing I saw as we pulled into the station was a brand new branch of TK Maxx. It must be difficult for those who lived through the DDR to know how to feel: I’m sure they’re pleased for the younger generations who have freedom and no memory of how things were, but are they also jealous that they themselves were cheated out of breakfast on the pavement? I think I could forgive them if so.

I’m not sure, though, I can forgive statements like this one from Graeme Knowles, Dean of St Paul’s cathedral:

We have no lawful alternative but to close St Paul’s cathedral until further notice. We are concerned about public safety in terms of evacuation and fire hazards and the consequent knock-on effects which this has with regards to visitors. With so many stoves and fires and lots of different types of fuel around, there is a clear fire hazard. Then there is the public health aspect which speaks for itself. The dangers relate not just to cathedral staff and visitors but…

Yadda yadda yadda. I’m writing this in London, England, on Monday, 24th October, 2011.

Much of the information here is taken from Leipzig 1989: A Chronicle by Doris Mundus, published by Lehmstedt Verlag. The photos of the candlelit march and the occupied pews are also taken from the book; they’re credited to Gerhard Weber and Gerhard Gäbler respectively. The two other photos are by Lucy Munro.